Has it really been fifteen years since Tim Wakefield arrived in Boston? His endorsement of Just for Men signaled that the answer was yes (even as the product erased the evidence of that passage of time). Wakefield’s consistency anchored the Red Sox through personnel changes in the locker room and management suite, helped the team win two World Championships, and witnessed the rejuvenation of Red Sox fandom. And he’s done it all as the predominant practitioner of baseball’s oddest pitch, a remnant of the eccentricities, inventiveness, and wildcat nature of the sport’s early days: the knuckleball.

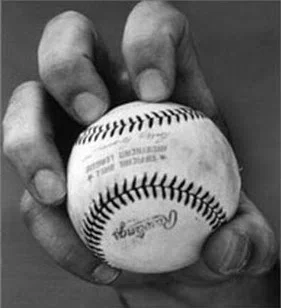

“The mystery of the knuckleball is ancient and honored,” Roger Angell wrote in 1976. “Its practitioners cheerfully admit that they do not understand why the pitch behaves the way it does; nor do they know, or care much, which particular lepidopteran path it will follow on its way past the batter’s infuriated swipe. They merely prop the ball on their fingertips (not, in actual fact, on the knuckles) and launch it more or less in the fashion of a paper airplane, and then, most of the time, finish the delivery with a faceward motion of the glove, thus hiding a grin.”

Befittingly, the elusive pitch claims elusive origins. As Angell noted, its name is a misnomer. The knuckleball is properly thrown by digging one’s fingernails into the leather of the ball. The knuckles splay upward, but have nothing to do with execution. To this day baseball scholars haven’t pinpointed the mad scientist who actually devised the knuckleball. The pitch, first observed in the early 20th Century, has alternatively been credited to Lew Moren and Ed Cicotte (of Black Sox infamy). No matter. For all the world the pitch is sui generis.

The mere fact that a pitch, some 20-30 miles per hour slower than a typical major-league fastball, could bewilder the game’s greatest hitters testifies to its singular unpredictability. The perfect knuckleball flutters through the air without completing a full rotation. It casually bends around the strike zone, sometimes in, sometimes out, sometimes down and sometimes all of these. A major leaguer’s lightning swing doesn’t register. The tortoise wins the race.

Then the knuckleball becomes the catcher’s problem. “Catching a knuckleball is easy,” Bob Ueker famously noted, “wait until it stops rolling and then pick it up.” The knuckleball spawned specialized catcher’s gear, an outsized glove that’s more satellite dish than mitt. Hoyt Wilhelm’s knuckler inspired his manager, the Orioles’ Paul Richards, to create a massive catcher’s mitt he called “Big Bertha;” the Hall of Fame proudly displays it to this day.

Knuckleballers have never dominated the game, but the pitch has persisted, even though it has only a small cadre of adherents in each generation of players. In 1945, the Washington Senators started four “flutterball” pitchers, and finished second in the American League. But the flutterball never entered baseball’s mainstream, and by the mid-1960s, when Phil and Joe Niekro broke into the majors, its practitioners had dwindled. The Niekro brothers both made fine—and long--careers as flutterballers: the pitch allowed Phil Niekro to complete a Hall of Fame career at age 48. (Brother Joe didn’t enjoy such durability and retired at the tender age of 43.) Yet by the late 1980s, the Niekros lacked an heir apparent and their delicate specialty faced extinction. Enter Tim Wakefield.

When a scout told him he would never make the majors as a position player, Wakefield took up the knuckleball as an act of hope and desperation, saying he needed to be sure he’d done everything he possibly could to make a career in baseball. The pitch won him a spot on the Pittsburgh Pirates and a single sterling season before he lapsed into two years of control problems. But after the Pirates released him and the Red Sox signed him, he began to work with Joe and Phil Niekro, a tutelage it’s tempting to imagine in a God-touches-Adam’s finger sort of way, especially considering the results. In his first 17 games with the Sox, Wakefield went 14-1 with a 1.65 ERA, and pitched 6 complete games.

It hasn’t all been that Olympian since then—that wouldn’t be the way of the knuckleball—but it’s often been very good. This winter, Wakefield worked out with Eri Yoshida, the 18-year-old knuckleballer who at 16 became the first woman drafted by a Japanese professional men’s team and who is now playing in an American independent league. It would be an astonishing and unlikely accomplishment if she made it to the majors in America. But this is the knuckleball. Anything can happen. And grins—both behind gloves and in the stands—are guaranteed.